Ahead of the fourth anniversary of the West London tower block fire in which 72 people perished, Emma Dent Coad examines some of the outstanding unresolved issues

Housing and re-housing

The official figures relating to re-housing of households made homeless by the Grenfell Tower fire were presented to the Housing and Communities Select Committee on April 26th 2021.

Of 201 households from Grenfell Tower and Walk, 195 households have now moved into permanent homes, and six households are in “high quality Temporary Accommodation”. Of 89 from the “wider Grenfell community” who wished to move (mostly people from the adjoining walkways), 13 are in Temporary Accommodation.

But is 195 the correct figure? Many of these households were overcrowded, or had adult children who needed to live on their own after the fire.

It is usually stated that 300 homes were bought by the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea (RBKC) to re-house the Grenfell homeless families.

So if 195 households have moved into permanent housing, what has happened to the other 105 units? Local estate agents report that some were put back on the market.

The RBKC Annual Monitoring Report (AMR) is a Planning document that reports on progress or otherwise on housing targets.

In the year 2017/18, the Council lost a total of 151 homes at Grenfell Tower and Walk. Strangely, this is not accounted for. While they list other losses such as amalgamations, bedsits to studios, etc., they do not account for an actual loss.

Nor does itsubtract housing units that have been demolished prior to development. So for example, Catalyst’s Wornington Green in North Kensington is the first post-war estate to be developed. The original estate comprised 541 flats and houses. These are all being demolished and replaced by double the number with private flats.

Yet they don’t subtract losses through demolition. However, they use the replacement flats as “net additional affordable” homes.

They are decidedly not “net additional”. They are replacements.

Another mystery in relation to Wornington Green is the number of affordable homes to be built at the end of the process. In 2010 we were told that the estate was “short of 201 bedrooms” and development was essential to house overcrowded families; it gained planning permission on that basis. However we have recently been told that the final number of affordable homes will be “541, maybe 15-20 extra”. So it is clear, as we always knew, that the guarantee of return for families who had been ‘decanted’ was not deliverable.

The target set by the Greater London Assembly’s London Plan for new homes of all kinds in the borough was 733 per year up to 2021; from this year onwards it has been reduced to 448. Given that so many “net additional” are questionable, you have to wonder if they will ever deliver them.

The Council has numerous plots of land they could build on, but it requires political will. The Mayor of London has committed £33m to build affordable housing in RBKC. So far two sites are in heavily polluted areas, next to the Westway, and on Shepherd’s Bush roundabout. How many of the future sites will be on polluted or toxic land?

The Common Housing Register

Some years ago RBKC reduced the number of people on the so-called Waiting List, as it was deemed unlikely that many on the list would ever be housed permanently. The list had been at around 6,000 and was reduced to about 2,500, and the name changed to “Common Housing Register”.

In mid-2021 the Waiting List is now 3,500 households. There are 2,500 households in Temporary Accommodation (TA), but they have no record of any overlap, so it is unclear whether or not there are 6,000 households waiting to be rehoused. They have no record of how many family members are in each household, if there are more single people, or more larger families, maybe with a grandparent living with them. They do not have a record of how many of these households include family members with disabilities. They do not have a record of age range and potential need for accessibility in future. They do not have a record of the ethnicity of households in TA.

Rather than making genuine efforts to provide more housing for residents on low incomes, RBKC seems determined to keep them out of the borough in ‘permanent temporary’. The longest period reported of a family living in TA was 13 years.

There are various reasons why RBKC could be more interested in keeping families in TA than housing them permanently. One is that people in TA are charged full market rent that they can’t afford, so their rent is paid by the government via the Council. If somehow the Council can find a cheaper home for them to rent, they keep the surplus. This surplus, made by moving homeless households out of the borough goes to ‘protect frontline services’. These services are still being cut year by year.

A proposal in the Council Budget for 2021/22 is to spend £40m on buying Temporary Accommodation over the next three years. So it seems they cannot afford to buy or otherwise provide homes in RBKC, but are prepared to spend millions moving our residents out of the borough into so-called Temporary Accommodation.

Empty homes

RBKC is fond of stating that the borough is the most densely populated in London, which isn’t strictly true. It may be the most densely built. Occupation of these properties is another matter entirely.

The Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government states there are 1,916 empty properties in the borough, of which 1,179 are long-term, over six months. There are 650 empty for two years, and 57 that have been empty for over 10 years.

The Council has begun a dance of death with government over the possibilities of changing the law. Given their strong links with supporters who are landlords, this lobbying seems performative rather than purposeful.

Empty Council properties are another matter altogether. We seem to have gone back ten years to a time when I was on the Kensington and Chelsea Tenant Management Board, when ‘voids’ were getting out of control and the time between lets to get them to ‘Lettable Standard’ was indefensible.

Covid lockdowns and restrictions have obviously impacted heavily on this, but the problem is long-standing.

The “Empty Homes Strategy and Council Voids” paper to the Housing and Communities Select Committee of May 24th 2021 says the target for re-letting Council properties is 28 days.

The average re-let time for 395 properties in 2019/20 pre-Covid was 136 days. The average for 304 properties in 2020/21 was a drastically improved 82 days, but still over three times the target. 15 properties have been empty for more than six months.

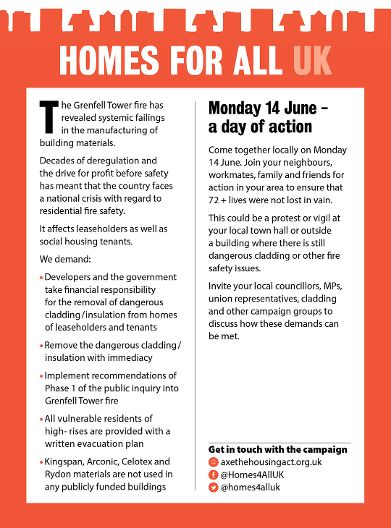

Fire safety

The Council owns over 9,000 residential units, in 979 buildings. Clearly there is a lot of work to be done to bring all our Council housing stock up to scratch, and there is the ongoing issue of leaseholders having to go through a separate and legally determined consultation process as they contribute to costs, which is time-consuming.

However, I was surprised to see, if I have calculated correctly, that around 300 of these properties have not been inspected, and this includes several of our sheltered housing blocks. My calculation is that 7 out of 11 sheltered housing blocks have “no data” or they still “need to inspect”.

We should not lay blame on the RBKC officer team. Four years after the Grenfell Tower, and when the new Leadership team of senior Tory Councillors stated they wanted RBKC to be an “exemplar” borough, they are still prepared to understaff some teams while paying £1m minimum for PR, and £3m-4m a year for legal support, to protect the Council from accountability, or indeed, prosecution.

Grenfell funding

From the earliest days after the fire, there was a perception that money was being misdirected, that the ‘wrong people’ were getting access to government or Council funds, and that a lot was mis-spent at the Council on high-earning officers who were out of touch with what was happening on the ground, and on endless consultations and schemes that barely ‘touched the sides’ of the problem.

The government-appointed Independent Task Force confirmed this perception via five very critical Reports, the fourth of which said the Council was “going backwards” in its relations with residents. “Consultation fatigue” was also cited, but RBKC continue with a programme of punitive and often purposeless consultation.

The issue of trust in the Council existed before the fire, in the immediate aftermath, and prevails as an ongoing problem, which it seems is being tackled by simply doing ‘more of the same’.

After some persuasion, RBKC’s Audit and Transparency Committee published a report on Grenfell Funding, on May 25th 2021. Clearly this will be the first word and not the last: there is a lot missing from this report.

There was no reference to the five Independent Task Force reports that laid out emphatically where the Council was going wrong. As the reports stated, there was very little progress in relation to its recommendations, and misdirected funding was flagged up.

The Report to the Audit and Transparency Committee states that the Council has spent £405.8m, of which £105m came from the government. The Public Inquiry is costing £100m. So over half a billion pounds has already been spent, and early estimates were that the fire would cost the public purse, in total, £1bn once it is ‘over’, whenever that might be. I haven’t seen cost estimates for the police investigation that will step in as soon as the Inquiry final report is published.

There are numerous issues that have been skirted around in this report. In July 2019 RBKC, against recommendations from the Task Force, decided to abolish the Grenfell Recovery Scrutiny Committee. The various ‘work streams’ were to be dispersed to the relevant business groups, with a reduced directorate in charge of overseeing the Dedicated Service – the service giving personal support to Grenfell-affected people. But it also reduced accountability, and this report confirms this perception.

There is no full breakdown of Grenfell expenditure in this report. The specific budget lines for senior staff, and for numbers of staff, are not included. The Audit Letter to the Audit and Transparency Committee in November 2020 stated there are 300 staff working on Grenfell services, but they are not mentioned here. The Task Force stated that the “Directorate [is] expensive and unsustainable in the long run”. This has been ignored.

The report states that 700 people use the Dedicated Service, of which 96% are satisfied – some find this hard to believe. There is no mention whatever of the effects of Covid to this service, and if – as related anecdotally – ‘contact’ can sometimes mean a brief phone call.

There is no breakdown of spending on PR and communications. They did spend £1.6m on “engagement” in 2019/20, but there is no assessment of outcomes.

There is no breakdown of spending on the building, services and staff of the premises at Old Court Place which have been the subject of numerous inquiries. Just how much has been spent on the sixth floor space for Grenfell United, aside from the rent of £500k a year? They have permanent staff – what do they do, and how much are they paid? The Council missed a valuable opportunity to report all these sums in detail unequivocally and to vindicate this group once and for all from many of the accusations that have circulated.

There is no explanation of the various organisations and what they do, nor how they are funded. What is “Grenfell Education”, “Grenfell Foundation”, “Grenfell Trust”? Are they charities or campaign groups? Is there a Value for Money assessment of where money has been spent?

There are too many people in the area who say they have had “little or no support”. They have a right to know where and how £.5bn funds have been spent.

An organisation facing potential prosecution for corporate manslaughter should not be marking its own homework.

Environmental and soil testing

When the neighbourhood was full of acrid smoke during the fire and days afterwards, people grabbed face-masks kindly donated by a local business. We feared in the early hours, when some people were coughing uncontrollably, that this could cause long-term damage to health.

We heard about the ‘Grenfell cough’. The Council denied it existed. But local GPs reported 70 patients with a cough six months and over after the fire, which was uncontrollable and included coughing blood.

Residents of buildings next to the fire were also concerned about the potential toxicity of burnt insulation material that fell into their balconies and gardens up to half a mile from the Tower, and potentially toxic dust in their homes. They were concerned that fire effluents or tiny asbestos particles in their parks, gardens and vegetable plots could poison them, causing long-term health problems, including cancer.

One local group invited a world renowned Professor to take samples. Early results looked very bad. This was reported to the Council. The Leader of the Council denied knowledge of this research. It was eventually (and reluctantly) agreed that the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government would undertake environmental and soil testing.

They visited various vegetable plots to take samples in October 2020 – 40 months after the fire. We have been told to expect the results later this summer. This will be the fifth season that vegetable growers are eating produce from their plots, worried that they are poisoning themselves.

Public Inquiry

The Public Inquiry has revealed some totally jaw-dropping attitudes to fire safety, where officers, elected representatives and others have admitted to lying about combustibility, have shown utter contempt for those they are paid to serve, and a complete lack of compassion or understanding – or even genuine regret – for the enormity of what happened on 14 June 2017.

The best and most extensive reporting on the Inquiry is by Inside Housing.

Inequality

I proved in 2014, by delving into statistics from the Office of National Statistics, that K&C is “the most unequal borough in Britain”. In October 2020 I updated that with a more detailed report, using ONS statistics and others from recognised organisations.

The neighbourhood around Grenfell Tower has, for the first time, been included in the “top six most multi-deprived” neighbourhoods in London. The first most deprived is Kensal Town in Golborne Ward.

All the stats are included here.